19. References

Section 1. Introduction

[1] Gardner, David G., Dolores M. Shoback, and Francis S. Greenspan. Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2007. 243-44. Print.

[2] Guyton, Arthur C., and John E. Hall. “Thyroid Metabolic Hormones.” Pocket Companion to Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2001. 590. Print.

Section 2. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)

[3] Shier, David, Jackie Butler, and Ricki Lewis. Hole’s Human Anatomy & Physiology. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2004. 482. Print.

[4] Kumar, Vinay, and Ramzi S. Cotran. Robbins Basic Pathology: With Studentconsult Access. Elsevier Saunders, 2004. 728. Print.

[5] Kumar, Vinay, and Ramzi S. Cotran. Robbins Basic Pathology: With Studentconsult Access. Elsevier Saunders, 2004. 727. Print.

[6] Blanchard, Kenneth H., and Marietta Abrams-Brill. What Your Doctor May Not Tell You about Hypothyroidism: a Simple Plan for Extraordinary Results. New York: Warner, 2004. 12. Print.

[7] Eckman, Ari S. “TSH Test: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia.” National Library of Medicine – National Institutes of Health. 19 May 2010. Web. 18 Aug. 2010.

Section 3. Beyond TSH

[8] Andersen, Stig, Klaus M. Pedersen, Niels Henrik Bruun, and Peter Laurberg. “Narrow Individual Variations in Serum T(4) and T(3) in Normal Subjects: a Clued to the Understanding of Subclinical Thyroid Disease.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 87.3 (2002): 1068-072. Print.

[9] Guyton, Arthur C., and John E. Hall. “Thyroid Metabolic Hormones.” Pocket Companion to Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2001. 586-587. Print.

[10] Arafah, Baha M. “Increased Need for Thyroxine in Women with Hypothyroidism during Estrogen Therapy.” The New England Journal of Medicine 344.23 (2001): 1743-749. Print.

[11] McPhee, Stephen J., and Maxine A. Papadakis. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2010. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2010. 1005. Print.

[12] Fischbach, Frances Talaska. Manual of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests for PDA. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. 441-451. Print.

[13] Brady, David M. “Thyroid and Adrenal Disorders.” Lecture. The Role of Thyroid, Adrenal and Othe Endocrine Dysfunctions in Chronic Illness. Boston. 29 Oct. 2005. The Role of Thyroid, Adrenal and Other Endocrine Dysfunctions in Chronic Illness. Moss Nutrition. 94-100. Print.

[14] Ibid., 94-100.

[15] Fischbach, Frances Talaska. Manual of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests for PDA. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. 453. Print.

[16] Pizzorno, Lara, and William Ferril. “Chapter 32, Thyroid.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 644. Print.

[17] Guyton, Arthur C., and John E. Hall. “Thyroid Metabolic Hormones.” Pocket Companion to Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2001. 561. Print.

Section 4. Not all doctors treat hypothyroidism the same way

[19] Gardner, David G., Dolores M. Shoback, and Francis S. Greenspan. Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2007. 243-44. Print.

Section 5. Low TSH induced hypothyroidism

[20] Miller, Marcus N., Cheryl K. Burdette, and Richard S. Lord. “Chapter 10 Hormones.” Laboratory Evaluations for Integrative and Functional Medicine. Ed. Richard S. Lord and J. Alexander. Bralley. Duluth, GA: Metametrix Institute, 2008. 552. Print.

Section 6. Iodine deficiency

[21] Guyton, Arthur C., and John E. Hall. “Thyroid Metabolic Hormones.” Pocket Companion to Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2001. 590. Print.

[22] Fitzgerald KN, Nelson-Dooley C, and Richard S. Lord. “Chapter 3 Nutrient and Toxic Elements.” Laboratory Evaluations for Integrative and Functional Medicine. Ed. Richard S. Lord and J. Alexander. Bralley. Duluth, GA: Metametrix Institute, 2008. 104. Print.

[23] Meletis, Chris D., and Nieske Zabriskie. “Iodine, a Critially Overlooked Nutrient.” Alternative and Complementary Therapies 13.3 (2007): 132-36. Print.

[24] Smyth, Peter P.A. “Role of Iodine in Antioxidant Defence in Thyroid and Breast Disease.” Biofactors 19.3-4 (2003): 121-30. Print.

[25] Kessler, Jack H. “The Effect of Supraphsiologic Levels of Iodien on Patients with Cyclic Mastalgia.” The Breast Journal 10.4 (2004): 328-36. Print.

[26] Ristic-Medic, Danijela, Zlata Piskackova, Lee Hooper, Jiri Ruprich, Amelie Casgrain, Kate Ashton, Mirjana Pavlovic, and Maria Glibetic. “Methods of Assessment of Iodine Status in Humans: a Systematic Review.” American J of Clin Nutr 89.6 (2009): 2052s-069s. Print.

[27] Christianson, Alan. “Iodine’s New Paradigm: More…or Less?” Naturopathic Doctor News & Review 6.8 (2010): 8-10. Print.

[28] Moss, Jeff. “A Perspective on High Dose Iodine Supplementation – Part V – The Japanese Experience with Dietary Iodine.” Moss Nutrition Report 218 (1 Dec. 2007). Print.

[29] Konno, K., H. Makita, K. Yuri, and K. Kawasaki. “Association between Dietary Iodine Intake and Prevalence of Subclinical Hypothyroidism in the Coastal Regions of Japan.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 78 (1994): 393-97. Print.

[30] Anguiano B et al. Uptake and gene expression with antitumoral doses of iodine in thyroid and mammary gland: Evidence that chronic administration has not harmful effects. Thyroid. 2007;17(9):851-859.

[31] Ibid.,

[32] Moss, Jeff. “A Perspective on High Dose Iodine Supplementation – Part VII – Can High Dose Iodine Suppress Iodine Uptake Into the Thyroid?” Moss Nutrition Report 221 (1 Apr. 2008). Print.

[33] Moss, Jeff. “A Perspective on High Dose Iodine Supplementation – Part VIII – Some “Big Picture” Thoughts on All That I Have Written in This Series So Far” Moss Nutrition Report 221 (1 Jun. 2008). Print.

[34] Moss, Jeff. “A Perspective on High Dose Iodine Supplementation – Part XII – Laboratory Analysis To Determine Need And Overall Series Conclusions Moss Nutrition Report 228 (1 Aug. 2009). Print.

Section 7. Auto immune hypothyroidism (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis)

[35] Tomer, Yaron, and Terry F. Davies. “Infection, Thyroid Disease, and Autoimmunity.” Endocrine Reviews 14.1 (1993): 107-20. Print.

[36] Brady, David M., Alexander Bralley, and Richard S. Lord. “Chapter 7 Hormones.” Laboratory Evaluations for Integrative and Functional Medicine. Ed. Richard S. Lord and J. Alexander. Bralley. Duluth, GA: Metametrix Institute, 2008. 426-29. Print.

[37] Petru, G., D. Stuenzner, P. Lind, O. Eber, and JR Moese. “Antibodies against Yersinia Enterocolitica in Immunogenic Thyroid Diseases.” Acta Medica Austriaca 14.1 (1987): 11. Print.

[38] Hanaway, Patrick. “Chapter 26 Clinical Approaches to Gastrointestinal Imbalance: Balance of Flora, GALT, and Mucosal Integrity.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Ed. David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 444-53. Print.

[39] Brady, David M., Alexander Bralley, and Richard S. Lord. “Chapter 7 Hormones.” Laboratory Evaluations for Integrative and Functional Medicine. Ed. Richard S. Lord and J. Alexander. Bralley. Duluth, GA: Metametrix Institute, 2008. 413-466. Print.

[40] Ibid.,

[41] Ibid.,

[42] Ibid.,

[43] Ibid.,

[44] Ibid.,

[45] Ibid.,

[46] Nichols, Trent W., and Nancy Faass. Optimal Digestion: New Strategies for Achieving Digestive Health. New York, NY: WholeCare, 1999. 62-63. Print.

[47] Lukaczer, Dan. Textbook of Functional Medicine. By David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 462-68. Print.

Section 8. Celiac disease

[48] Purcell, Gretchen P. “What Makes a Good Clinical Decision Support System.” BMJ 330 (2005): 740-41. Print.

[49] Fasano, Alessio. “Celiac Disease- How to Handle a Clinical Chameleon.” The New England Journal of Medicine 348.25 (2003): 2568-570. Print.

[50] get from celiac notes – every perosn dxed w/ celia 14 others have not, or just cite whole seminar

[51] Fasano, Alessio, and Carlo Catassi. “Current Approaches to Diagnosis and Treatment of Celiac Disease: An Evolving Spectrum.” Gastroenterology 120 (2001): 636-51. Print.

[52] Nicoletta, Ansaldi, Tiziana Palmas, Andrea Corrias, Maria Barbatto, Rocco Mario D’Altglia, Angelo Campanozzi, et al. “Autoimmune Thyroid Disease and Celiac Disease in Children.” J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 37.1 (2003): 63-66. Print.

[53] Brady, David M. “Thyroid and Adrenal Disorders.” Lecture. The Role of Thyroid, Adrenal and Othe Endocrine Dysfunctions in Chronic Illness. Boston. 29 Oct. 2005. The Role of Thyroid, Adrenal and Other Endocrine Dysfunctions in Chronic Illness. Moss Nutrition. 125. Print.

[54] Hyman, Mark. “Chapter 26, Clinical Approaches to Environmental Inputs.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Ed. David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 370. Print.

[55] Corrao, Giovanni, Gino Roberto Corrazza, Vincenzo Bagnardi, Giovanna Brusco, Carolina Ciacci, and Mario Cottone. “Découvrir / Discover Refdoc INIST Diffusion 2, Allée Du Parc De Brabois F-54514 Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy Cedex France Phone: +33 (0)3 83 50 46 64 Fax: +33 (0)3 83 50 46 66 Nous Contacter Contact Us Faire Une Nouvelle Recherche Make a New Search Lancer La Recherche Commander Ce Document Ok Order This Document Ok Titre Du Document / Document Title Mortality in Patients with Coeliac Disease and Their Relatives: a Cohort Study.” Lancet 358 (2001): 356-61. Print.

[56] Hyman, Mark. “Chapter 26, Clinical Approaches to Environmental Inputs.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Ed. David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 369. Print.

[57] Ibid,.

Section 9. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (APS)

[58] Betterle, Corrado, and Renato Zanchetta. “Update on Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes (APS).” Acta Bio Medica 74 (2003): 9-33. Print.

Section 10. Why the body may want to make less thyroid hormone

[59] Werner, Sidney C., Sidney H. Ingbar, Lewis E. Braverman, and Robert D. Utiger. Werner & Ingbar’s the Thyroid: a Fundamental and Clinical Text. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000. 281-295. Print.

Section 11. Euthyroid sick syndrome and low T3 syndrome

[60] Berkow, Robert, and Mark H. Beers. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck &, 1999. 86. Print.

[61] Ibid.,

[62] Ober, K. Patrick. Endocrinology of Critical Disease. Totowa, NJ: Humana, 1997. 155-73. Print.

[63] Brady, David M. “Thyroid and Adrenal Disorders.” Lecture. The Role of Thyroid, Adrenal and Othe Endocrine Dysfunctions in Chronic Illness. Boston. 29 Oct. 2005. The Role of Thyroid, Adrenal and Other Endocrine Dysfunctions in Chronic Illness. Moss Nutrition. 96. Print.

Section 12. Anti-thyroid diets

[64] Bland, Jeffrye S., and David S. Jones. “Chapter 32 Clinical Approaches to Hormonal and Neuroendocrine Imbalances: Cellular Messaging, Part II- Tissue Sensitivity and Intracellular Response.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Ed. David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 590-609. Print.

[65] Felig, PF. “The Thyroid: Physiology, Thyrotoxicosis, Hypothyroidism, and the Painful Thyroid,.” Endocrinology and Metabolism, Third Edition. Ed. RD Utiger. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995. 435-519. Print.

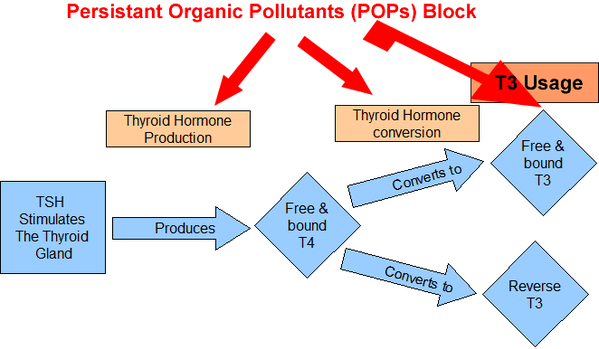

Section 13. Heavy metals, toxins and the liver

[66] txt fxn med pg 150

[67] “Persistent Organic Pollutants: A Global Issue, A Global Response | International Programs | USEPA.” US Environmental Protection Agency. 27 May 2010. Web. 23 Aug. 2010. <http://www.epa.gov/international/toxics/pop.html#pops>.

[68] txt fxn med ref 270, pg 601]

[69] ref 269, txt pfxn med 601 – think it is 269, typo was 379

[70] Sauvage, Marie-Frederique, Pierre Marquet, Annick Rousseau, Claude Raby, Jacques Buxeraud, and Gerad Lachatre. “Relationship between Psychotropic Drugs and Thyroid Function: A Review.” Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 149.2 (1998): 127-35. Print.

[71] Ibid.,

[72] Felig, PF. “The Thyroid: Physiology, Thyrotoxicosis, Hypothyroidism, and the Painful Thyroid,.” Endocrinology and Metabolism, Third Edition. Ed. RD Utiger. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995. 435-519. Print.

[73] Ibid.,

[74] Ibid.,

[75] Ibid.,

[76] Pizzorno, Lara, and William Ferril. “Chapter 32 Clinical Approaches to Hormonal and Neuroendocrine Imbalances: Thyroid.” Ed. David S. Jones. Textbook of Functional Medicine. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 647. Print.

[77] Bland, Jeffrye S., and David S. Jones. “Chapter 32 Clinical Approaches to Hormonal and Neuroendocrine Imbalances: Cellular Messaging, Part II- Tissue Sensitivity and Intracellular Response.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Ed. David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 590-609. Print.

[78] “How Your Thyroid Works – “A Delicate Feedback Mechanism”” Endocrine Diseases: Thyroid, Parathyroid Adrenal and Diabetes. – EndocrineWeb. Web. 23 Aug. 2010. <http://www.endocrineweb.com/thyfunction.html>.

[79] Pelletier, Catherine, Eric Doucet, Pascal Imbeault, and Angelo Tremblay. “Associations between Weight Loss-Induced Changes in Plasma Organochlorine Concentrations, Serum T3 Concentration, and Resting Metabolic Rate.” Toxicological Sciences 67 (2002): 56-51. Print.

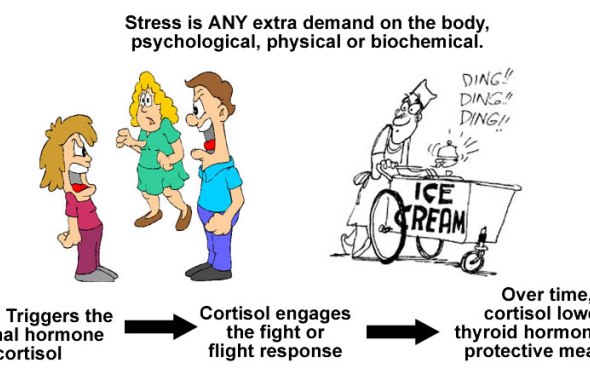

Section 14. The adrenals, stress, cortisol and low T3

[80] Guyton, Arthur C., and John E. Hall. “Thyroid Metabolic Hormones.” Pocket Companion to Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2001. 473. Print.

[81] Selye, Hans. The Stress of Life. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976. 74-78. Print.

[82] Stratakis, CA, and GP Chrousos. “Neuroendocrinology and Pathophysiology of the Stress System.” Ann N Y Acad Sci. 771 (1995): 1-18. Print.

[83] Wilson, James L. Adrenal Fatigue: the 21st Century Stress Syndrome. Petaluma, CA: Smart Publications, 2001. 27-44. Print.

Section 15. Blood sugar, estrogen and hormonal balance

[84] Guyton, Arthur C., and John E. Hall. “Thyroid Metabolic Hormones.” Pocket Companion to Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2001. 523-524. Print.

[85] Felig, PF. “The Thyroid: Physiology, Thyrotoxicosis, Hypothyroidism, and the Painful Thyroid,.” Endocrinology and Metabolism, Third Edition. Ed. RD Utiger. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995. 435-519. Print.

[86] Ibid.,

[87] Lang, Janet R. “Balancing Femail Hormones Naturally (part 1).” Lecture.

[88] Obal F., and Kruegar, JM. “Hormones, cytokines, and sleep.” Coping with the Environment: Neural and Endocrine Mechanisms. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. 331-349. Print.

Section 16. Graves disease and Hyperthyroidism

[89] Gardner, David G., Dolores M. Shoback, and Francis S. Greenspan. Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2007. 248-55. Print.

[90] Ibid.,

[91] Ibid.,

[92] Hull, Janet Starr. Sweet Poison: How the World’s Most Popular Artificial Sweetener Is Killing Us– My Story. Far Hills, NJ: New Horizon, 2001. Print.

Section 17.

[93] Pizzorno, Lara, and William Ferril. “Chapter 32 Clinical Approaches to Hormonal and Neuroendocrine Imbalances: Thyroid.” Ed. David S. Jones. Textbook of Functional Medicine. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 644-47. Print.

[94] Bland, Jeffrye S., and David S. Jones. “Chapter 32 Clinical Approaches to Hormonal and Neuroendocrine Imbalances: Cellular Messaging, Part II- Tissue Sensitivity and Intracellular Response.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Ed. David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 590-609. Print.

[95] Aktuna, D., W. Buchinger, W. Langsteger, E. Meister, H. Sternad, O. Lorenz, and O. Eber. “Beta-carotene, Vitamin A and Carrier Proteins in Thyroid Diseases.” Acta Med Austriaca 20 (1993): 17-20. Print.

[96] Bland, Jeffrye S., and David S. Jones. “Chapter 32 Clinical Approaches to Hormonal and Neuroendocrine Imbalances: Cellular Messaging, Part II- Tissue Sensitivity and Intracellular Response.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Ed. David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 590-609. Print.

[97] “25-hydroxy Vitamin D Test: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia.” National Library of Medicine – National Institutes of Health. Web. 25 Aug. 2010. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003569.htm>.

[98] Schurgers, LJ, HM Spronk, BA Soute, PM Schiffers, JG Demey, and C. Vermeer. “Ion of Warfarin-induced Medial Elastocalcinosis by High Intake of Vitamin K in Rats.” Blood 109.7 (2007): 2823-831. Print.

[99] Masterjohn, C. “Vitamin D Toxicity Redefined: Vitamin K and the Molecular Mechanism.” Med Hypotheses 68.5 (2006): 1026-034. Print.

[100] Pizzorno, Lara, and William Ferril. “Chapter 32 Clinical Approaches to Hormonal and Neuroendocrine Imbalances: Thyroid.” Ed. David S. Jones. Textbook of Functional Medicine. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 644-47. Print.

[101] Bland, Jeffrye S., and David S. Jones. “Chapter 32 Clinical Approaches to Hormonal and Neuroendocrine Imbalances: Cellular Messaging, Part II- Tissue Sensitivity and Intracellular Response.” Textbook of Functional Medicine. Ed. David S. Jones. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005. 590-609. Print.

[102] Benvenga, Salvatore, Antonino Amato, Menotti Calvani, and Francesco Trimarchi. “Effects of Carnitine on Thyroid Hormone Action.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1033.1 (2004): 158-67. Print.

[103] Friedman, Michael. Fundamentals of Naturopathic Endocrinology: Complementary and Alternative Medicine Guide. Toronto, ON: CCNM, 2005. 94. Print.